Early presence in Canada

While Chinese were present – mostly on the West coast – when Canada became a country in 1867, the change of politics meant little to them or their status as aliens. They were subjected to rules under the colonial administration of British Columbia until 1871, when the British colony became a Canadian province.

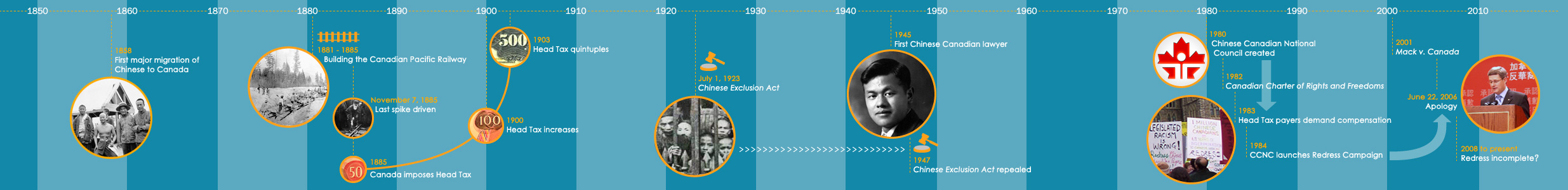

Chinese labourers working on the railways, first in the United States on the Central Pacific Railroad and then from 1881 to 1885 on the Canadian Pacific Railway, were often given the epithet of having a “Chinaman’s chance” of surviving the dangerous work involved; especially if they were tasked with handling explosives used to blast through rock to make way for the iron road.

However, use of the term as it pertains to the history of law and legislation in Canada has had the most profound impact on the development of the Chinese Canadian identity and community.

“Chinaman’s chance”

The first reference to the term “Chinaman’s chance” may have its roots in a landmark California Supreme Court decision dating back to 1854, in which a white man was acquitted on appeal of murdering a Chinese man.

The case, People v. Hall, held that a conviction for George W. Hall, described by the court as “a free white citizen,” for murdering a Chinese miner named Ling Sing was faulty because Chinese witnesses had testified against the defendant. At the time, California law regulating criminal proceedings provided that “no black or mulatto person, or Indian, shall be allowed to give evidence in favor of, or against a white man.” It was further held that “Indian” included anyone of the Mongoloid race and that “black” was anyone other than white.

Clearly, the Chinese had no status under the law at the time; giving the Chinese witnesses to the murder of Ling Sing no standing in court – and creating a “Chinaman’s chance,” or nothing at all, for all Chinese before the courts. Violence committed against the Chinese by whites could not be prosecuted under the law.

The ruling in People v. Hall left the Chinese in a legal vacuum; with no standing given to them in legal proceedings, they could not assert any legal entitlements or claims in court. The decision set the course of injustice that was to rule affairs where the Chinese were concerned.

Their existence in a legal no-man’s land south of the border also dogged the Chinese as they followed the gold rush trail north to British Columbia’s Fraser River Valley. The Chinese remained segregated from white society, both in the cities and towns, as well as in labour and mining camps, even though their numbers were smaller and of no threat to Europeans.