Unequal rights

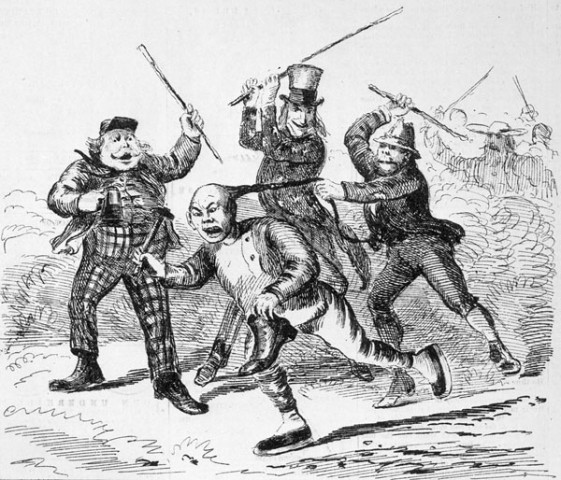

Chinese were not the only victims of racist laws in early Canada. Decisions on status, privileges and rights related to “alienage,” or foreign origin, by the courts and the Privy Council set legal precedents for all Asian immigrants, particularly those who came to Canada through Pacific portals.

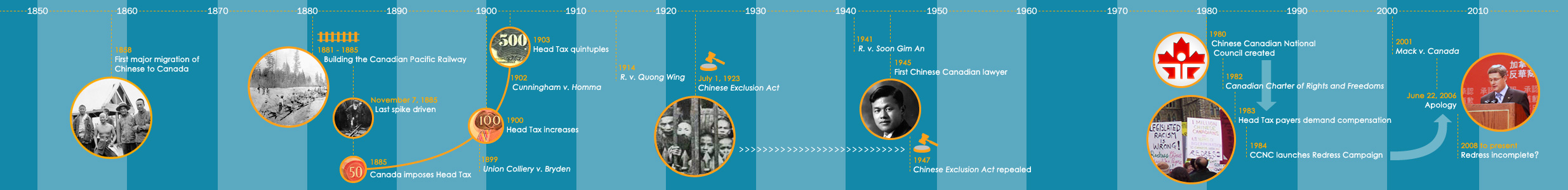

Two cases, Union Colliery v. Bryden (1899) and Cunningham v. Homma (1901), would set the course of legal discrimination against Chinese and Japanese in Canada, and reinforce other decisions and laws that equally affected South Asians and First Nations – particularly in their exclusion from the electoral franchise.

Union Colliery v. Bryden (1899)

In 1899, the B.C. courts heard a case in which the B.C. Coal Mines Amendment Act (1890) was challenged when John Bryden, a shareholder in Union Colliery, wanted the company to bar Chinese from holding certain jobs of trust and responsibility at its coal-mining operations.

The 1890 amendment to the Coal Mines Act had prohibited Chinese people from being employed in coalmines below ground; the provisions to the Act were allegedly based on safety concerns about Chinese workers’ lack of English language skills.

Section 4 of the amended Act stated that: “No boy under the age of twelve years, and no woman or girl of any age, and no Chinaman, shall be employed in or allowed to be for the purposes of employment in any mine to which this Act applies below ground.”

In Union Colliery v. Bryden, the company argued that the provincial government had exceeded its authority to prohibit employment of Chinese people in mines. The matter was decided by the Privy Council, which agreed with the company and struck down the Coal Mines Amendment Act.

In its decision, the Privy Council stated that its members were “of the opinion that the whole pith and substance of the enactments of s. 4 of the Coal Mines Regulation Act . . . consists in establishing a statutory prohibition which affects aliens or naturalized subjects, that therefore trench upon the exclusive authority of the Parliament of Canada.”

Historian Victor Lee observes: “The Privy Council in that case seemed to say that the federal government had exclusive jurisdiction over laws directed towards Chinese people in Canada.”

Cunningham v. Homma (1902)

However, in a court challenge by members of the Japanese Canadian community three years later over their exclusion – as well as Chinese and First Nations – from the B.C. voters’ lists, the Privy Council held that it was within the province’s power to withhold voting rights.

Within a year of joining Confederation, as one of its first orders of business as a Canadian province, British Columbia passed its Qualification and Registration of Voters Act (1872) that excluded “Chinese” and “Indians” from the provincial electoral franchise. At the time the legislation was enacted, the province’s population was made up of nearly 62 per cent First Nations and Chinese people. People of British origin represented just under 30 per cent. In 1896, “Japanese” were also excluded from the voters’ lists. Disenfranchisement was racially based.

In 1900, Tomekichi “Tomey” Homma, a naturalized Canadian of Japanese parentage tried to have his name added to the B. C. voters’ list. He failed in his attempt, because of the discriminatory election laws. Homma took his case to court and he won a short-lived decision, which upheld the right of naturalized Canadian citizens to vote, regardless of their ethnic origin. The B.C. government appealed to the B.C. Supreme Court, which upheld the lower court’s decision. Undaunted, the government appealed again to the Privy Council, then Canada’s final court of appeal.

The Privy Council in Cunningham v. Homma (1901), ruled in favour of the government and Homma lost the case as well as his right to vote.

Disenfranchised

British Columbia’s disenfranchisement of First Nations, Chinese and Japanese was reaffirmed in subsequent amendments and in the Provincial Voters’ Act, and extended in 1907 to “Hindus,” or all South Asians.

Being excluded from the provincial voters’ lists had far-reaching implications for these ethno-racial groups, because provincial laws regulating many of the professions also required candidates to be eligible voters. In the case of the Chinese, British Columbia continued to exclude them from the political process, creating them as “perpetual aliens,” and barring their participation in municipal elections and even running for positions as school board trustees.

Historian Victor Lee further comments in his analysis of these Privy Council decisions on federal and provincial jurisdictions that Canada’s Constitution Act (1867) “gave the federal government the right to determine what shall constitute an ‘alien’ or what is ‘naturalization,’ (but) it did not give the federal government the right to determine what privileges are attached to these statuses.”

In 1908, the Province of Saskatchewan also disenfranchised all residents belonging to the Chinese race in An Act respecting Elections of Members of the Legislative Assembly, Saskatchewan (1908) .

Exclusion from the provincial electoral franchise was debilitating for the Chinese Canadian community, many of whom in later years were either naturalized or born in Canada, as the federal Parliament, until 1948, based its own law on electoral participation on inclusion in the provincial lists.